Dafen oil painting Village

Brushstrokes of Reality: The Beauty and Cruelty of Dafen

Inspired by the documentary China’s Van Goghs (2015) by director Yu Haibo and the Nanfengchuang article “Shenzhen Dafen: The Cruelty and Beauty of an Art Village” (January 13, 2018), I was struck by the discovery that in a city often mocked as a ‘cultural desert’ like Shenzhen, there exists a place as seemingly out of sync as Dafen Village. I was deeply moved. On November 28, 2021, I invited a friend to join me on a midday trip, spending the afternoon exploring Dafen Village and seeking to understand its current reality.

Before setting out, I did plenty of research. Most online reports about Dafen Village date back to before 2018, a time when China’s Van Goghs had garnered international attention and won numerous awards. Yu Haibo’s photo series Dafen Oil Painting Village even won second prize at the 49th World Press Photo Contest. These awards, aside from their own prestige, placed this small urban village under the global spotlight, attracting waves of media coverage. After 2018, however, public attention waned. The few recent reports and videos mostly focus on changes in appearance, environmental improvements, and shifts in government policy toward Dafen. But I was after something more. This trip had three main purposes:

- To visit Zhao Xiaoyong, the main character of China’s Van Goghs. I wasn’t sure if I would find him, nor what I would say if I did. But the unknown held its own allure, and I wasn’t anxious about it.

- To observe how the environment of Dafen had changed — whether in terms of artist migration, tourist volume, infrastructure, or painting styles.

- To visit the Dafen Art Museum. It’s clear that the Shenzhen government wants to reshape Dafen into a national hub of artistic and cultural production, and any place of such ambition needs a landmark building. The museum plays that role. From online images, its modern architecture seemed jarringly out of place — something I felt compelled to see in person, as if on a pilgrimage.

To get to Dafen Village from Shenzhen University, one must take Metro Line 3 and disembark at Dafen Station. The trip takes a little over an hour, yet it didn’t feel that long. On the final stretch, the train runs above ground — more like light rail — and through the windows, one can see a giant sign below: “Shenzhen Dafen Oil Painting Village.” This marks the symbolic entrance. On either side of the tracks rise rows of densely packed high-rises — not quite the cyberpunk skyscrapers of Nanshan, but still oppressively tall and dense. The view perfectly matches the wide-angle shots seen throughout China’s Van Goghs. The only difference? In the film, the skies were bleak and overcast; when I visited, the sun was shining.

After exiting the station, we had to walk a little farther to reach the heart of the village. Although geographically close, the area leading into Dafen felt like a completely different world — wide, modern roads devoid of any trace of oil painting. It was only later, upon leaving, that I realized how stark this contrast truly was.

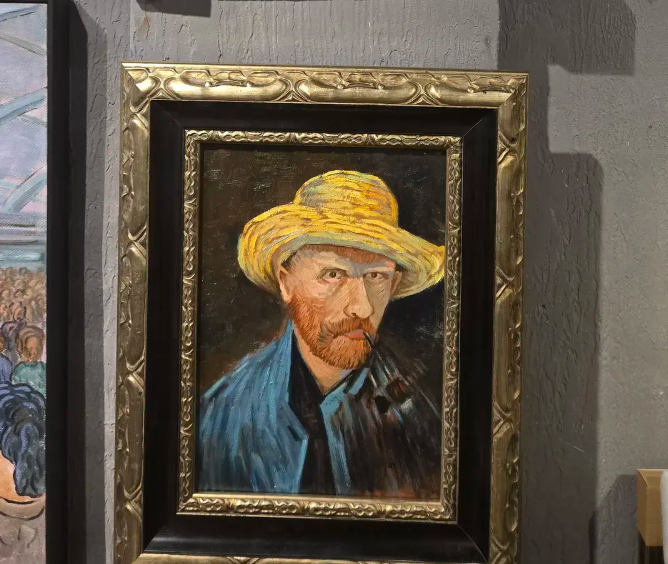

Once inside the village, oil paintings were everywhere — hanging from walls and corners, displayed at storefronts, even laid out directly on the ground. Van Gogh reproductions were the most common, followed by Monet. Nearly every shop carried Sunflowers, Starry Night, and Van Gogh’s self-portraits. According to the reports I read — and based on my own understanding — why Van Gogh and Monet? For one, Dafen’s early orders were almost exclusively for Van Gogh reproductions. These were easy to sell — most buyers were European, and for them, Van Gogh was like a Bible of oil painting. Unable to afford originals, they turned to replicas. Secondly, Van Gogh’s works are easier to paint — and by “easier,” I mean more manageable for the artists in Dafen. Abstract art is notoriously difficult to create, especially Monet’s impressionist works, which demand a mastery of color that defies pure technique. But for painters copying from a photo, they’re quite doable. Oil paint is also forgiving: a mistake can simply be painted over. For many Dafen artists, reproducing Van Gogh is a rite of passage.

That day, I spoke to a painter who was working on a piece inside one of the shops. He told me most artists here come from rural areas or construction jobs with no prior training. To learn, they usually apprentice under a master, starting with small tasks and gradually learning to paint. They typically begin with Van Gogh. Within a few months, they can paint independently — though not with great refinement. Mastery takes much longer.

One popular feature in Dafen today is oil painting workshops for tourists. It’s also a vital source of income for many local artists, especially after the pandemic caused a sharp decline in overseas orders. One painter said, “Luckily, more domestic customers have started appreciating oil paintings. Some people order them as home décor during renovations. But it’s still far less business than a few years ago.” The workshops are simple — a few easels and stools, ready-mixed paints, and a stack of sample artworks. Visitors pick a painting to copy, and the owner offers occasional guidance. The finished products are usually decent. Prices range from 50 to over 100 yuan. It’s a unique Dafen experience, and one I personally regret missing due to time constraints.

My friend and I spent a long time watching the painters at work — smooth brushstrokes, occasional swipes with palette knives — movements repeated thousands of times with practiced ease. That’s what moved me most. Painting here is part of daily life — like playing music, sipping tea, or sketching a scene. It stands in stark contrast to the hustle of Shenzhen’s high-tech urbanity. But don’t mistake it for some artistic utopia. Harsh reality lives here too. The attention brought by China’s Van Goghs didn’t fundamentally change much. Many artists came here with dreams of making a living from painting, but most eventually gave up and returned to reality. Zhao Xiaoyong told me this himself (yes, I found him — more on that shortly).

Earlier, I mentioned most artists in Dafen are self-taught migrants. But there’s another group — academically trained artists. I saw several painters working in quiet corners, blending in completely with their surroundings. On inquiry, I learned some were art school graduates or even master’s students. In my mind, these were the kind of people who gave lectures in well-lit galleries. Yet here they were — perhaps driven by necessity, or maybe seeking inspiration, or simply using Dafen as a creative retreat. Who knows? But their presence felt quietly bittersweet.

Beyond the visuals, one sensory detail stands out: the smell. The scent of oil paints and acrylics permeates everything. If you’re used to seeing oil paintings in pristine galleries under spotlights, you’d be shocked. Here, art is stripped of its lofty aura and brought uncomfortably close. Not in a romantic “art meets life” way, but in a jarring overlap of authenticity and artificiality. You can sense the fakeness in many of the works — even I, not a professional, could tell. Copies are still just copies. After seeing a hundred versions of Sunflowers, my friend and I were tempted to call most of them “poor imitations.” Still, I don’t mean to say art must be detached from everyday life to have value. Quite the opposite: art’s value comes from life. Van Gogh’s Starry Night, Sunflowers, and Wheatfield with Crows all move us because they distill the emotion and vitality of life itself.

The biggest surprise of the day was stumbling upon Zhao Xiaoyong’s studio. It looked like the same one from the documentary, though now it had a fresher design. A China’s Van Goghs poster hung at the entrance. Alongside Van Gogh replicas were many of Zhao’s own works. He was in the inner room, painting a Van Gogh self-portrait, with an unfinished cup of tea on the table and Debussy’s Clair de Lune softly playing from a speaker. I couldn’t believe it was him — not until my friend pointed it out. I had assumed he’d “made it big” from the film and left this place behind. Nanfengchuang reported that after six years of filming, Zhao rose to fame in 2017, and his paintings that once sold for a few hundred yuan now fetched as much as 12,000. But when I stepped into the room, he barely looked up before returning to his work. That’s when I realized: Van Gogh doesn’t just live in paint or on paper — he lives in the hearts of a few people.

Zhao was happy to chat. I rambled on about my interpretation of Van Gogh, the documentary, and my impressions of Dafen. He listened quietly, sometimes nodding, occasionally responding, then calmly returning to his painting. His brush added layer by layer to the self-portrait. I looked around at his original works, full of Van Gogh’s influence, and recalled that scene in the documentary — Zhao traveling all the way to the Netherlands, only to find his painting not in a gallery, but in a souvenir shop near the Van Gogh Museum. His eyes glistened with tears. So close to Van Gogh — yet so far. “To become Van Gogh, to become Van Gogh!” I don’t know if he still dreams of that. I didn’t dare ask. But he did seem more at peace than in the film.

As I was leaving, he shared more stories of Dafen and even added me on WeChat. He had recently been interviewed by the podcast Story FM and sent me several episodes. That alone made the trip unforgettable.

Van Gogh sold only one painting in his lifetime and died in poverty. Everyone in Dafen paints Van Gogh, but no one wants to become him. Everyone carries a fire within them, but passersby only see the smoke.

This ends my account — though the experience is far richer than what I could ever write. If you visit Dafen yourself, you’ll find it far more vivid and alive than anything I could describe. I’ll include links to the references at the end.